“Over a decade ago ago, nine of Kimberly Harris’ acquaintances told the police she burglarized a neighbor’s house in Jackson, Miss. After her arrest, the police released her because “there was no evidence.” Her accusers later went to jail for “false accusation,” Harris, now 38 years old, told the Mississippi Free Press in late October. She was at a criminal record expungement clinic organized by the nonprofit Mississippi Volunteer Lawyers Project and their partners at Mississippi e-Center at Jackson State University.

Harris told the Mississippi Free Press she was at the event “to get an expungement on a 12-year-old charge that’s been dismissed, and it’s stopping me from being able to work in hospitals and stuff like that. Once you’ve been fingerprinted, you cannot work in the hospital.” An arrest is usually accompanied by fingerprinting, creating a criminal record.

Harris said the hospitals she applies to usually ask her to bring legal proof of her case’s dismissal following a background check that brings up the arrest record. “They’ll tell you that if you have the abstract, they’ll bring you back and they’ll let you work,” she said. “But over the years, I bring them back (but) they don’t ever, ever call me back again.”

On Oct. 28, expungement clinic organizers asked attendees to come with proof of payment of fines and fees and an abstract of the adjudication from the municipal or justice court if it was a misdemeanor offense. Those with a felony case were asked to bring the sentencing order or dismissal order from the circuit court, the indictment and proof of payment of fines and fees.

When people come to the events, the organizers judge whether each charge is ripe for expungement based on applicable laws and whether they qualify for the pro bono service by falling below 200% of the federal poverty guideline. The lawyers will prepare the motion for the client to take to the circuit clerk in the county where the issue arose and pay a fee. In the case of a felony, the individual must bring a copy of the motion stamped by the circuit clerk to the district attorney; the individual will wait a few days and then regularly and repeatedly call the clerk’s office to ask if the judge has signed the expungement order. After that, they send the order to the Mississippi Department of Public Safety.

Harris told the Mississippi Free Press that though the law enforcement agency dropped the charge against her soon after, that arrest record has been an albatross on her for over a decade.

“Once you’ve been fingerprinted, it stays on your record, even if you haven’t been charged with the crime,” Harris said. “The charge was never a charge. It was an arrest, but I didn’t get charged, and it’s been on my record for 12 years.”

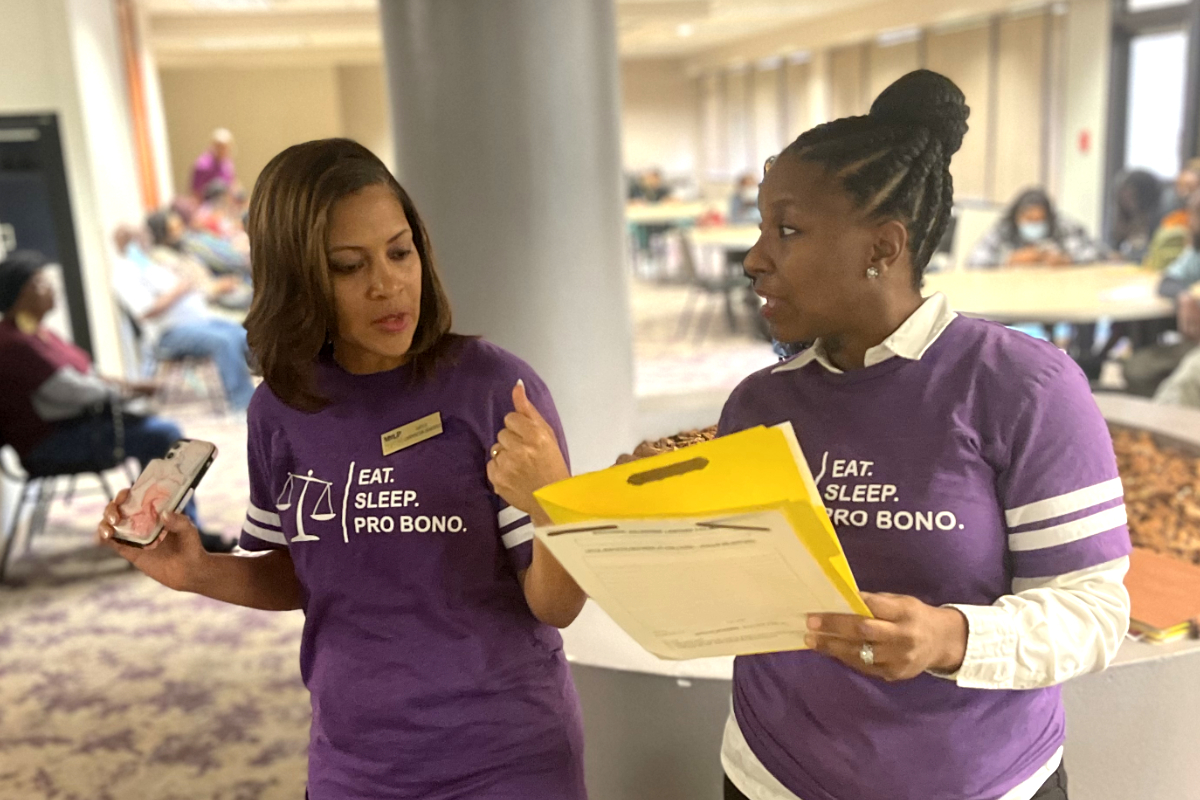

Criminal record expungement is vital to help people enjoy socio-economic benefits, Mississippi Volunteer Lawyers Project Executive Director Gayla Carpenter-Sanders told the Mississippi Free Press at the Oct. 28, 2022, event. She lost the runoff election for Hinds County Chancery Court judge on Nov. 30, 2022, and has continued working with the nonprofit.

“This program is important because we have a lot of individuals out there who are not able to access suitable housing or suitable jobs and they have been disenfranchised with regards to voting because they have criminal infractions on their record,” she said. “An expungement, which is actually a civil remedy, allows them to get those matters erased off of their records so that when they apply for housing, apply for a job or re-register to vote, once someone pulls up their record, those items are off of there, and they’re no longer obstacles to whatever it is that that person is trying to seek.”

“We’ve had individuals who have come to us who are trying to get into nursing school who couldn’t because of a misdemeanor on their record,” she said. “We have had people who have come to us who could not get custody of grandchildren in youth court proceedings because they had criminal infractions on their record; we’ve been able to help those individuals with being able to get into nursing school, being able to get custody of their grandchildren in youth court proceedings.”

In a 2012 paper, University of California, Davis School of Law Professor Gabriel J. Chin described the lasting social impact of having criminal records as “civil death.”

“For many people convicted of crimes, the most severe and long lasting effect of conviction is not imprisonment or fine,” he wrote. “Rather, it is being subjected to collateral consequences involving the actual or potential loss of civil rights, parental rights, public benefits, and employment opportunities.”

“The commonly used term ‘mass incarceration’ implies that the most typical tool of the criminal justice system is imprisonment,” he explained. “Indeed, there are two million people in American prisons and jails, a huge number, but one which is dwarfed by the six-and-a-half million or so on probation or parole and the tens of millions in free society with criminal records.”

‘A Multi-Step Process’

Carpenter-Sanders said that her organization conducted expungement clinics in different parts of Mississippi to help people legally eligible for such benefits. While speaking to the clients gathered on Oct. 28, she explained what happened once the Department of Public Safety got the judge’s order and said she advised them to regularly call the circuit clerk to find out the status of the case and explained what would happen once they sent the order to the Department of Public Safety.

“What I don’t want you doing is running the risk of having it lost in the mail, and you can’t get a copy of the order, OK,” she said. “Because what happens is once that order is signed by the judge, the clerk’s office will go ahead and immediately erase that out of their system and shred those documents. You can’t go back and get a copy of the court order because it’s gone.”

“Now, once you get the court order, you’ve got one more step, and the step that you take is sending it to the Department of Public Safety,” she said. “The Department of Public Safety is who’s going to send it to the FBI, send it to all the clerks’ office, send it to all the arresting agencies, any detention centers or whatever, they’re going to send those documents—the expungement order—out so that they can erase it from their system. There’s a multi-step process.”

In Mississippi, the statute permits the expungement of the first misdemeanor offense without any waiting period and one felony offense five years after conviction, dependent upon the offender petitioning the court after completing all punishment and fine payment. People can petition the court for an order to erase records of arrests that did not lead to any charge, case dismissal, dropping of charges, or a not guilty verdict, all not ending in a misdemeanor or a felony offense conviction, without any waiting period.

Arson, drug trafficking, violent crimes, some driving-under-the-influence offenses, being a convicted felon in possession of a firearm, failure to register as a sex offender, voyeurism, witness intimidation, abuse, neglect, and exploitation of a vulnerable person and embezzlement are crimes the law excludes from the possibility of expungement.

A bad check offense, possession of a controlled substance or paraphernalia, false pretense, larceny of consigned motor fuel, malicious mischief and shoplifting are mentioned explicitly in Mississippi statutes as expungeable.

“The effect of the expunction order shall be to restore the person, in the contemplation of the law, to the status he occupied before any arrest or indictment for which convicted,” the law says. With the expungement, no person will be guilty of lying if they don’t mention their arrest, indictment or conviction when asked unless it’s to see if they’re a first-time offender, the law says.

‘Petition-based Process is Costly’

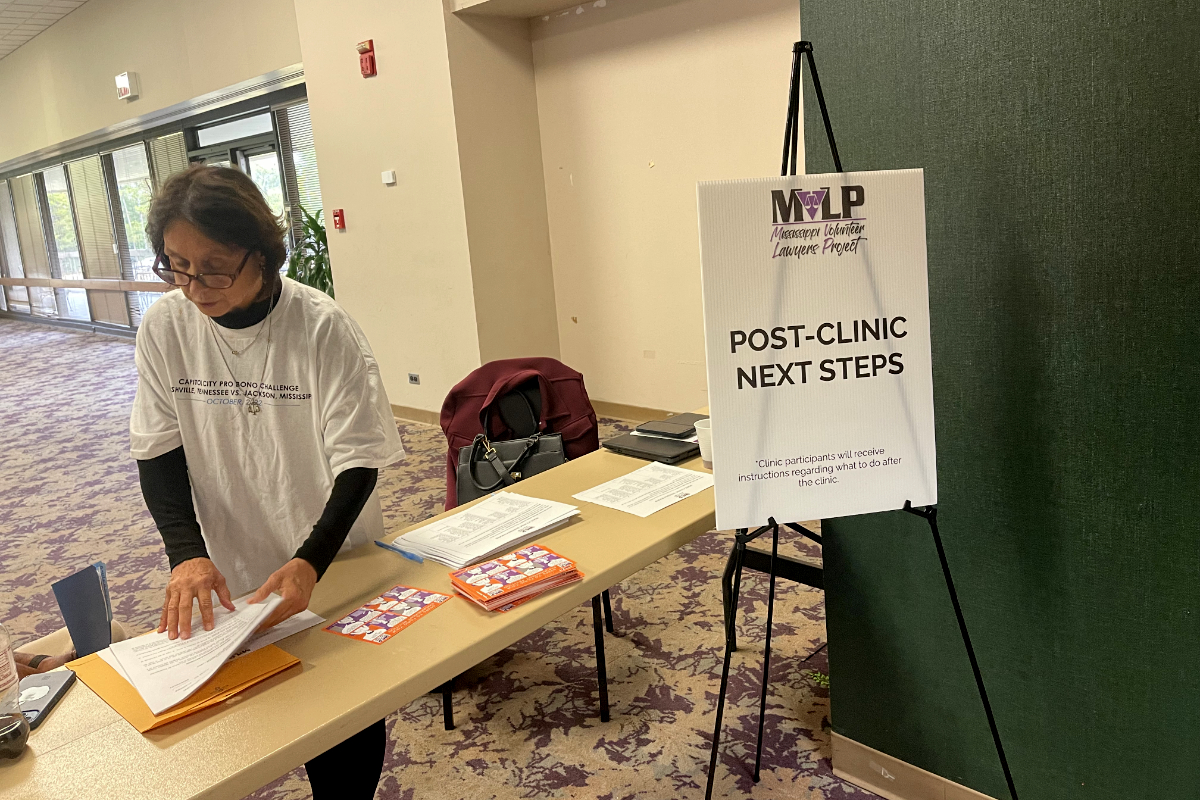

The organizers dubbed the October expungement clinic a competition between Jackson, Miss., and Nashville, Tenn., offices of five law firms of Bradley Arant Boult Cummins LLP, Adams and Reese LLP, Butler Snow and Baker Donelson. Butler Snow Pro bono counsel Linda Seely, who came up with the idea, told the Mississippi Free Press that Jackson handily won the “Capitol City Pro bono challenge.”

The fact that there is a low uptake of expungement opportunities was a concern for Sudbury Consulting LLC founder Noella Sudbury, who told a panel on the Legal Services Corporation podcast “Talking Justice” in July 2022 that the difficulties people face to get records expunged are a cause. She helped push for the automation of the process in Utah to put the burden on the government to erase the criminal record without any action by the eventual beneficiary through the passage of the state’s Clean Slate Act.

Sudbury authored the bill to automate the expungement process in Utah, and the state’s legislature passed it unanimously in 2019, but the State delayed implementation until February 2022 because of COVID-19. Pennsylvania became the first state to put such a law into effect in 2019 after its passage the year before.

According to the website mycleanslatepa.com, “[o]ver 1.2 million Pennsylvanians have since benefited from Clean Slate automated sealing” and “over 40 million cases have been sealed, accounting for more than half of the charges in the courts’ database.”

“Clean Slate uses an automated process to identify and seal qualifying records,” the website says.

Sudbury explained that over the years, various states passed expungement laws, and “a component of these policies is automatic clearance or clean slate laws,” she said.

“The problem is that the petition-based process is costly, it’s complicated, most people need a lawyer to get through the process, [but] most people can’t afford a lawyer, and so that’s why you’re seeing these super low uptake rates all across states,” Sudbury said. “Even though there is that legal remedy available, most states don’t have a centralized process, and it’s very, very difficult and expensive to get through.”

Semantics Matters

Clean Slate Initiative National Campaign Manager Jesse Kelley, Right On Crime Oklahoma Director Marilyn Davidson, and Texas Director Nikki Pressley spoke in a Right On Crime podcast published Dec. 9, 2022, on the push for clean slate Laws.

Davidson said that the advocates in Oklahoma, which passed a clean slate law in 2022, had to pivot to using the word “automated” instead of “automatic” because of the connotation in lawmakers’ minds.

“A lot of people wanted to call this an automatic expungement bill,” she said. “We found out very early on that was not the best word to use for it because lawmakers would hear automatic and in their minds, they would think, ‘OK, the person doesn’t have to go through the normal checks that you do now to make sure that they qualify (and ensure) they don’t have any pending or new felonies,’ and so it made them really scared and skittish about it.”

“So it had to be a lot of practice and a lot of training with our advocates, so they don’t use the word automatic, they use the word automated, because it’s not—and I had to tell them many times—it’s not an automatic expungement; we’re not like saying let’s just put them on a list, and they’re done,” she continued. “It’s the same process. It’s just done through an automated computer system, so it made a big difference.”.

Clean Slate Initiative National Campaign Manager Kelley explained that advocates made a similar pivot in Louisiana for more effective communication. “They’ve been working on passing some clean slate bills for a couple of years now, but they’ve switched to saying a government-initiated process, which also makes a lot of sense since you’re moving away from an individual petition-based process.”

“But rhetoric is so important, as is educating lawmakers on what these policies actually do,” she said. “We have passed policies like this in eight different states, and we’re running campaigns now in (about) 12 more.”

‘This Low Uptake is Troubling’

Professors of law J.J.Prescott and Sonja B. Starr released the result of a decade of research on the effect of expungements on offenders in Michigan when both worked at the University of Michigan. Starr has since joined the University of Chicago Law School.

“The discouraging element of our findings is that, despite the apparent benefits of expungement, very few people—even among those who are eligible—actually obtain them,” Prescott and Starr wrote in their paper. “Our best estimate is that 6.5% of people who meet the legal requirements for expungement in Michigan obtain one within five years—a small fraction of what is already a small fraction of all those living with records, given the tight eligibility requirements.”

“This low uptake rate is troubling, but not shocking, given the procedural hurdles and expenses involved, the lack of legal counsel, the dearth of public information, and the fact that most people with records have limited resources for overcoming these challenges,” the professors added. “Unfortunately, all but a handful of states with expungement laws require individuals to apply for relief and give judges the discretion to deny them, so the situation is unlikely to be better in other states.”

‘They Live Their Whole Life With This Noose’

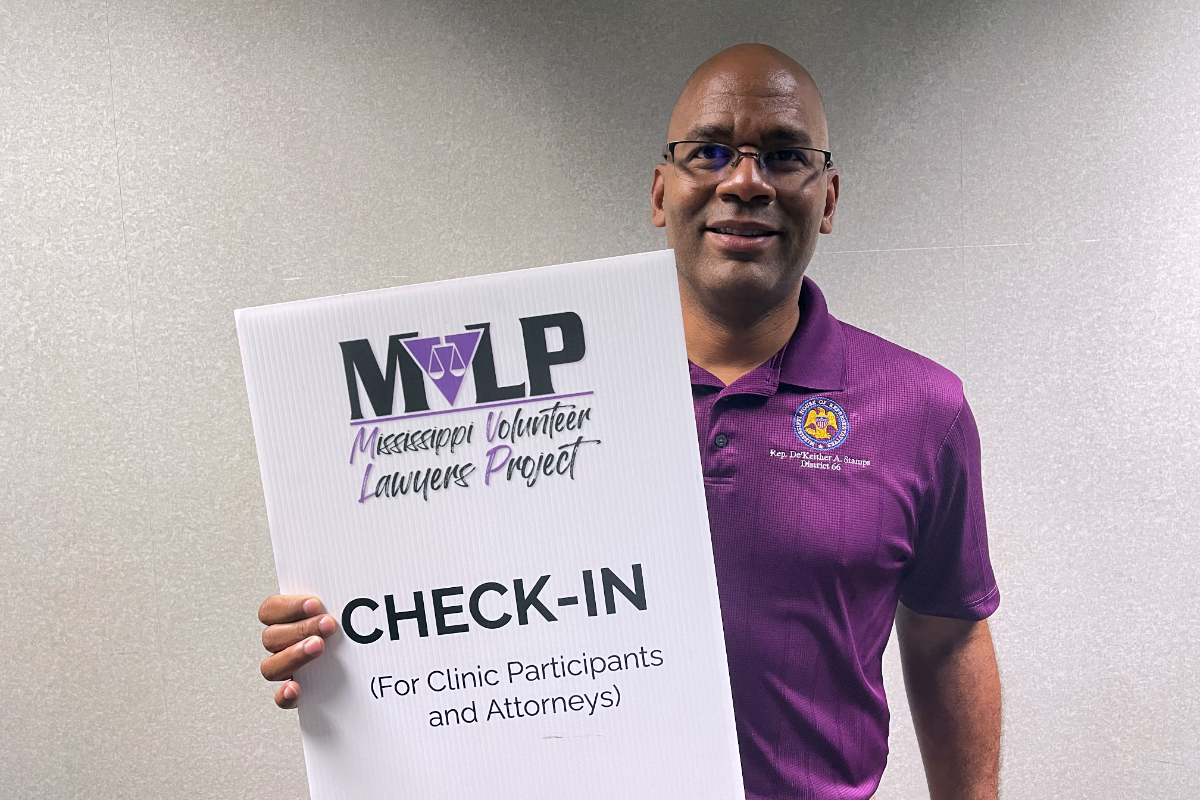

Mississippi State Rep. De’Keither Stamps, D-Jackson, partnered with the Mississippi Volunteer Lawyers Project for the Oct. 28 expungement clinic. He told the Mississippi Free Press over the phone a day before the event that “one big gap that we have is that people don’t believe that government processes work. So they live their whole life with this noose around their neck, not knowing that the noose can be removed or believing that it will get removed if they go through the process.”

He said that “you can get an unlimited number of misdemeanors expunged” in Mississippi, not just the first offense. The Miss. Code Ann. § 9-11-15 describes the expungement process for such misdemeanors at the justice court two years after the last conviction.

Mississippi expungement law changed in 2019 when the legislature added more felonies to the list of expungeable offenses, Carpenter-Sanders noted in her interview with the Mississippi Free Press.

“A lot of drug offenses can now be expunged from your record,” she said. “Mostly those crimes, like your violent crimes, are those crimes that cannot be expunged, like aggravated assault, murder, rape, arson, those types of crimes cannot be expunged. But most other crimes can be.”

From 2012 to 2021, Mississippi judges approved 8,875 expungement applications based on the data that the Administrative Office of Courts provided to the Mississippi Free Press.

‘It’s Just a Hassle To Try To Get Your Name Cleared’

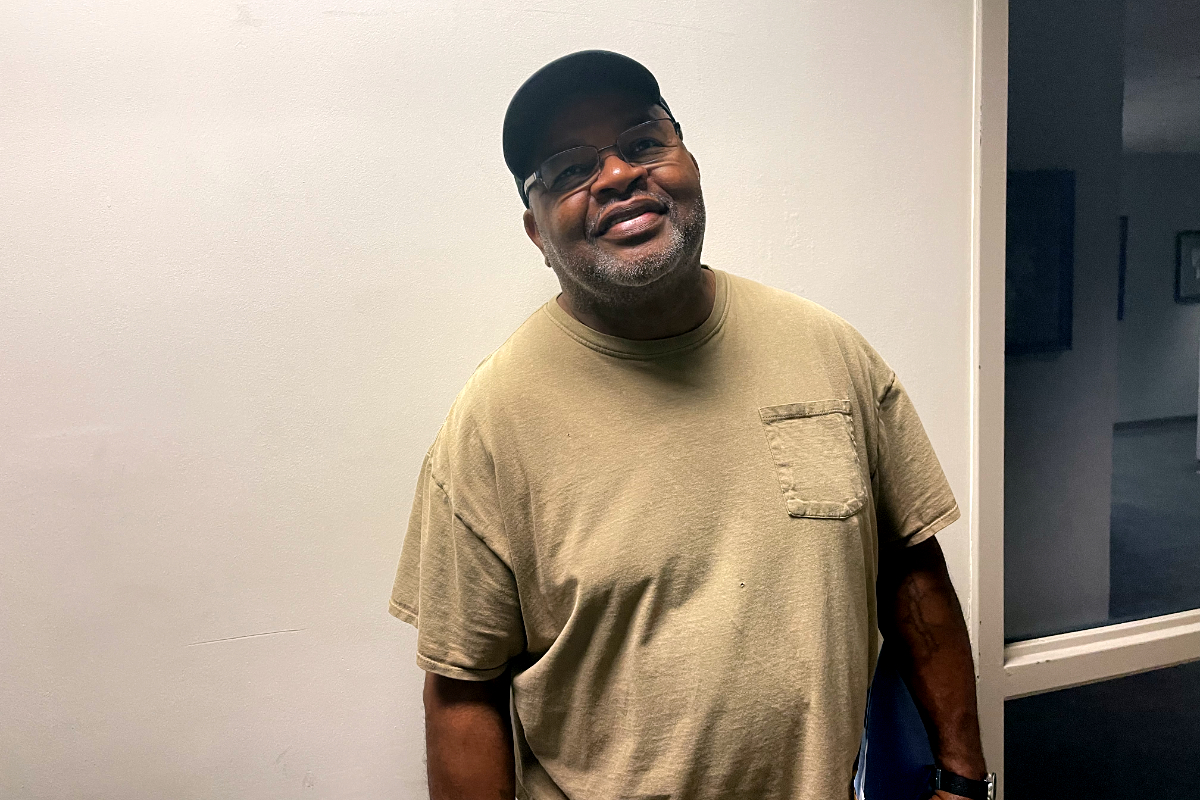

In 2011, Milton Pilate, now 58, said he refused to blow into a breathalyzer during a traffic stop in Jackson, Miss. “I was taking medication, and they thought I was under the influence of alcohol, but I was under medication, so I refused to blow, and the case got dismissed cause they found out with documentation that my story was accurate,” the truck driver told the Mississippi Free Press at the Oct. 28 expungement clinic.

He said it was only on Monday, Oct. 24, 2022, that he heard of the event and moved to get the necessary documents. “I went to Jackson Municipality Court, I asked for the court records, and I called the Hinds County Sheriff Department. They mailed me everything that they had on file, and I received them on Wednesday. So I got their documentation, everything they had, and I got the abstract of the records from the City of Jackson, Mississippi.”

He said his drive to get the expungement is so that the criminal record would not hinder him when he wants to change a job. “It just purges your records of being criminalized, like folks got to criminalize people, especially African-Americans,” he said. “We already got that serial type of being criminalized anyway, so therefore this is to clear all the records up.”

He thought that it would be hard to get his record cleared up without the help of the Mississippi Volunteer Lawyers Project.

“We had to go to court and pay attorney fees. … It’s just a hassle to try to get your name cleared through the court system (so) folks won’t criminalize you based on the face value of documentation they see at the court without going through the details of the event.”

‘Paying For A Clean Record’

Mississippi § 99-19-72 requires someone submitting an expungement petition to the court to pay a $150 filing fee. It costs $500 in Alabama, $550 in Louisiana, $285 in Minnesota, $300 in New Hampshire, $160 in New York, $175 in North Carolina, $281 in Oregon, $310 in South Carolina and $300 in West Virginia. University of Alabama School of Law Clinical Legal Instruction Associate Professor Amy F. Kimpel noted those costs in a May 2022 report on the burden of such payments on the indigent and titled it “Paying for a Clean Record.”

Kimpel argued that the fees create a barrier and lead to racial disparity in the uptake of the expungement process. “Again, conditioning records relief on payment of a large sum makes expungement more likely to be available to white people with records concentrating criminal records in communities of color and particularly in the Black community,” she said. “This is especially pernicious because employers tend to discriminate against Black individuals with records at higher rates than whites with criminal records.”https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/p6ZUe/5/

“Moreover, fee-based diversion and expungement programs are more prevalent in the South—the region which over half of Black Americans call home,” she said in the report.

In Mississippi, based on the Administrative Office of Courts data, from 2012 to 2021, Hinds County had the highest number of approved expungement cases at 1,139, corresponding to its position as the most populous county with a 2020 census population of 222,679.

However, when adjusted per capita using the 2020 census population, Hinds County ranks No. 10, with Lafayette, Tishomingo, Calhoun, Prentiss, Oktibbeha, Warren, Marion, Jackson and Lee counties coming ahead of Hinds County in that order. While Hinds County is majority Black, eight out of those top ten counties are majority white with expungements adjusted for population.

‘I Have to Get This Expunged Off My Records’

In 2010, Ezekiel Edwards, now 35, was driving his friend when they reached a traffic stop. He said they had a “couple of pounds of” marijuana in the vehicle. Both went to jail when neither owned up to being the drug owner. Later, his friend’s attorney convinced him to plead guilty to the possession crime.

“He owned up to everything. So there wasn’t any need for me to be even in the case, but since I got arrested with him, I pretty much went down with him,” Edwards told the Mississippi Free Press at the expungement clinic on Oct. 28.

Upon his release in 2010, Edwards entered a diversion program with the promise of the expungement of his arrest record. “I went through this little pretrial diversion for first-time offenders, and I stopped going. I was young. I didn’t know how important this would be. I know now,” he said.

He works as an overnight stocker and forklift operator at a retail outlet. He says he thought that with the medical marijuana law in Mississippi, “it should be an easy process for me to get this completely off my record. I mean, I wasn’t convicted, the case was dismissed, so why was it still on my record?” he said.

Though the State of Mississippi passed the medical marijuana bill earlier in 2022, the law did not legalize the product for recreational use and does not provide amnesty for those with cases involving marijuana possession. And while President Joe Biden issued a mass pardon for many federal marijuana offenses earlier this year, presidential pardons apply only to those convicted under federal laws, not state laws.

In a 2020 paper called “America’s Paper Prisons: The Second Chance Gap,” Santa Clara University School of Law Professor Colleen Chien suggested that the Clean Slate Initiative can help bridge the gap between those who could benefit from second chance laws and those who actually do. She explained that only 1-in-10 people who could benefit from second chance laws ultimately do so.

“Currently, in the majority of cases, second chance rights (to a clean record and to vote) are provided only after individual petitions are filed, evaluated case by case, and approved— processes that cannot readily scale to meet the enormous volume of eligible individuals,” she said. “Ruthless iteration and, where possible, simplification are needed to develop workable standards that can be applied and administered in imperfect data environments.”

“Burden shifting, from the individual to the state, and from decentralized to coordinated processes for identifying and administering relief, can also dramatically reduce the gap,” she said. “Finally, using automation, rather than petitions, can avoid the need for applicant awareness and wherewithal to determine eligibility and apply for relief. However, what is lost when processes become automatic deserves greater study.”

She estimates “that at least 20-30 million American adults, or 30–40% of those with criminal records, fall into the ‘second chance expungement gap,’ living burdened with criminal records that persist despite appearing to be partially or fully clearable under existing law.”

Ezekiel Edwards told the Mississippi Free Press at the expungement clinic that his 2010 arrest when he was 23 cast a long shadow.

“Today, I am here to get an old mistake of mine expunged off my record. Every traffic stop, it shows up, and for me to keep building and keep opening new doors, I have to get this expunged off my record,” he said. “It has a major effect on pretty much everything—me trying to get a new job, me trying to buy a home because I’m a new father, traveling.”

“I can’t do anything for the last 12 years, so it’s been a lot. It’s been very hard with this,” he said. “I wasn’t convicted; the case was dismissed, so why was it still on my record?”

Carpenter-Sanders acknowledged that there is a gap between what is available regarding expungement and the number of people taking advantage of it.

“They may just not know that the process exists,” she said. “You know, as much as we try to advertise—on the radio, in printed media, on television—some people still miss it, and you have to remember, you still have crimes constantly being committed, too.”

Carpenter-Sanders said those who could not attend the event could reach out to her organization or the Mississippi Center for Justice any time during the year. They both “do expungements all year round and across the entire state,” she said.

A National Increase in Expungement Laws

Noelle explained during the “Talking Justice” podcast that there has been an increase in expungement laws that various legislatures in the country have passed recently. “In the first half of 2021 alone, 25 states passed 50 different expungement laws.”

In 2021, lawmakers in the Mississippi Legislature proposed 22 expungement bills, but none became law. Mississippi Rep. Michael Evans, D-Preston, proposed House Bill 905, which would have provided that first-time offenders get “automatic” expungement “upon completion of all the terms and conditions of the sentence.”

In 2022, Rep. Nick Bain, R-Corinth, proposed House Bill 622, which, if passed, would have required the court to delete the record when “the person arrested was released, and the case was dismissed or the charges were dropped, there was no disposition of such case, or the person was found not guilty at trial.” Evans resubmitted the first-term offender expungement bill, H.B. 910, in 2022. Neither bill became law.

The Center for American Progress promotes the adoption of clean slate legislation at the federal and state levels and draws attention to a national campaign to relax expungement regulations. “From 2009 to 2014, at least 31 states and the District of Columbia expanded the scope and impact of expungement and sealing remedies in such ways,” the organization said. “A growing number of states are adopting ‘clean slate’ laws to automate expungement and sealing procedures, in recognition of the many barriers that can prevent eligible individuals from clearing their records when filing a petition is required.”

Addressing Public Safety Fear

The Center for American Progress says on its website that clean slate laws have widespread bipartisan and cross-racial support, including from 75% of Democrats, 65% of Republicans, 72% of African Americans and 73% of white Americans.

“Some may argue that since people with records are thought to pose a threat to public safety, employers, landlords, colleges, and the general public have a right to know about a person’s criminal record,” the organization said. “However, research suggests that individuals with sealed or expunged criminal records actually commit crimes at a lower rate than the general adult population.”

“In Michigan, for example, 99 percent of such individuals are not convicted of any felony, 99.4 percent are not convicted of any violent crime, and 96 percent are not convicted of any crime at all within five years of sealing their criminal records,” it says. “Furthermore, expungement and sealing can benefit the economy by providing individuals with criminal records a second chance at employment.”

In 2018, U.S. House Reps. Lisa Blunt Rochester, D-Ala., and Rod Blum, R-Iowa, introduced the first federal clean slate federal legislation with H.R. 6677, the Clean Slate Act of 2018. The bill would have allowed for the automated “sealing of a person’s federal record if they have been convicted of a nonviolent offense,” including for “misdemeanor drug crimes like simple possession” and federal nonviolent offense involving marijuana, Rochester said in a press release that year.

The bill never became law, despite being reintroduced by different federal lawmakers in subsequent years.

The bill proposed by Rochester and Blum would have allowed “individuals to petition the United States Courts to seal records for nonviolent offenses that are not automatically sealed, excluding violent crime and sex offenses,” Rochester said in 2018. “Currently, there is no system in place to allow individuals to have their record sealed at the federal level unless there is intervention from the President of the United States.”

“The Clean Slate Act will also help to reverse the long-term societal barriers and consequences created by U.S. drug enforcement policy over the past 40 years, while at the same time improving our economy, creating jobs, and providing hope to non-violent offenders who have earned a second chance,” she said at the time.

Rep. De’Keither Stamps said he supports having a clean slate law in Mississippi. “If it were up to me, if you committed an expungeable offense and you’ve met all the requirements of the court, it should happen automatically,” he said. “Because if you don’t meet the requirements, the courts act to continue to hold you accountable for those unmet requirements.”

“So why should the court not release you from those requirements once the requirements have been met?”

Carpenter-Sanders suggested adding more items to the list of expungeable offenses in the state.

“We had a gentleman who committed a violent crime in the late 1970s, and at the time, he was in his late twenties,” she said. “His family contacted us wanting to seek an expungement of his record because they were trying to get him into an assisted living facility and the assisted living facility would not accept him because of this criminal infraction on his record.”

“One thing that the state legislature may want to look at is the length of time that has passed since a person committed a violent crime to determine whether or not, you know, that person is rehabilitated and whether or not they deserve to have that taken off their record.”

Expungement More Cost Effective than Job Training, Says Researcher

Researcher Prescott said studies show that publicly-funded job-training programs increase annual wages by $832 for women and $471 for men, with the government spending $6,600 per person, while expungement recipients in Michigan experience wage gains of $4594 for women and $4295 for men.

He concluded that expungement has comparatively minimal costs, including running a background check, holding a court hearing, and processing the paperwork. “[A]nd these could very likely be reduced much further if the process were simplified or automated,” he said. “As an employment intervention, therefore, expungement appears superior to job training in terms of both its effectiveness and its price tag.”

Louisiana and Mississippi State Director for Right On Crime Scott Peyton supports automated expungement. He said it is the right move from a public-safety standpoint in his interview with the Mississippi Free Press on Dec. 6.

“So when we look at it through (the lens of) public safety, I think an expungement provides a public safety benefit as far as removing barriers for that individual when it comes to employment, when it comes to housing, and it also rewards and recognizes accountability and personal responsibility,” he said. “I do think expungement laws should be reasonably restrictive in order to keep that balance between public safety and redemption.”

He said some offenses need to stay on the record, including sex offenses, “where there’s data that supports that these individuals are more likely to recidivate, and this information is important to have available.”

“I do support clean slate legislation that automates expungements,” he said, as he pointed to Mississippi’s “complicated” process.

‘It Has Impacted Me A Lot’

It was 1974, and 17-year-old RC Anderson Jr. drove his car to go help some friends pick up goods from a house they had burglarized in Madison County. “I was the only one (among them) that had a car at the time,” he told the Mississippi Free Press on Oct. 28 at the expungement clinic. “They had broken into a house, and I went to pick up the stuff for them like a fool.”

“And when we got there to get the stuff, the police zeroed in on us,” Anderson added. “They were waiting for us to come get it. That’s how I got caught up in it.”

Anderson stayed at the Madison County Jail for six months, and after the court process, he received a three-year sentence, but was released after six months in Parchman.

Now that he is 65 and it has been decades since the crime, he still has a criminal record, and he went to the Mississippi e-Center to get help getting it erased.

“It has impacted me a lot,” Anderson told the Mississippi Free Press. “I can’t vote, I can’t buy a gun. I can’t own a gun, you know? And it’s quite a bit on you, when you ain’t got no way to protect yourself and your family because you can’t have a gun, man, with all the stuff going on now, it is hard.””